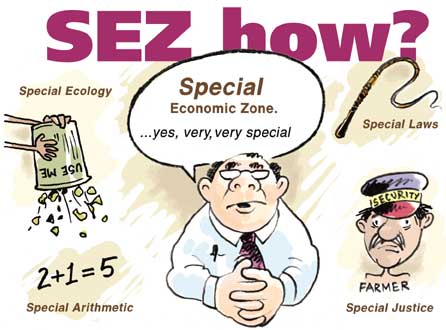

SEZs do not just have a patchy record when it comes to economic success; a host of academics and NGOs have produced multiple reports citing the crimes and harms produced by them.

These reports for example point to the most successful zones being the ones with low application of labour laws, prohibitions on the right to assembly, child labour, high death rates and little growth expansion in to the wider economy (Golpakrishnan 2007; McCullum 2011). Frey (2003:328-9) documents wider harms to society through reference to the environmental degradation in northern Mexico from the illegal and hazardous disposable of pollutants from the Maquiladora industry which in turn has implications for human health outside the SEZs. Agarwal (2010:88-93) exposes numerous illegal processes in India in relation to land acquisitions that benefited those with higher socio-economic status, national and local elites, while undercompensating, if they received the money, small and medium landholders. The Financial Action Task Force (2010) found numerous ways that SEZs can be used to illegally avoid tax and launder money: mostly through lax regulatory oversight by the authorities. While Golpakrishnan reports of thriving illegal sex industries in the SEZs of China.

Yet despite the numerous failing of SEZs globally and their propensity to crime and harm production their various promoters still fundamentally believe that these projects have the potential to uplift developing nations. Locating the problems with SEZs in the modern context of the need of host countries to reform and manage the zones sufficiently to meet capital’s needs. Farole and Akinci (2011:1) sum up this idea;

In the post crisis environment, in which competition for FDI likely will remain much more intense than it has been in the past, SEZs likely will continue to grow in importance. But it is not the existence of an SEZ regime, of a master plan, or even of a fully built-out infrastructure that will make the difference in attracting investment, creating jobs, and generating spillovers to the local economy. Rather, it is the relevance of the SEZ programs in the specific context in which they are introduced, and the effectiveness with which they are designed, implemented, and managed on an ongoing basis, that will determine success or failure.

By putting the emphasis on the state as the driver of SEZ polices they obscure the fact that under U.S. hegemony the state has been subjectivised to capital’s needs, and SEZs have played a role in this since the late 1940s.

Part I: The mainstream view of Special Economic Zones

References:

Agarwal, S. (2010). The Austerity of Neo-Liberalism: Peasant [De]Mobilization and Special Economic Zones in South India. thesis. [Online]. Available from: http://hdl.handle.net/1811/45739.

Gopalakrishnan, S. (2007). Negative aspects of special economic zones in China . Economic and Political Weekly. 42 (17). pp. 1492–1494.

McCallum, J.K. (2011). Export processing zones: Comparative data from China, Honduras, Nicaragua and South Africa. Geneva: International Labour Office.

Farole, T. & Akinci, G. (2011). Special economic zones: progress, emerging challenges, and future directions. Washington, DC: World Bank

Financial Action Task Force (2010). Money Laundering vulnerabilities of Free Trade Zones. Paris: Financial Action Task Force.

Frey, R.D. (2003). The transfer of core-based hazardous production processes to the export processing zones of the periphery: The Maquiladora centers of northern Mexico. Journal of World-Systems Research. 9 (2). pp. 317–354.